The First Four Kings Of Rome - b.C. 753-616

The history of Rome is that of a city which originally had only a few miles of territory, and gradually extended its dominions at first over Italy and then over the civilized world. The city lay in the central part of the peninsula, on the left bank of the Tiber, and about fifteen miles from its mouth. Its situation was upon the borders of three of the most powerful races in Italy, the Latins, Sabines, and Etruscans. Though originally a Latin town, it received at an early period a considerable Sabine population, which left a permanent impression upon the sacred rites and religious institutions of the people. The Etruscans exercised less influence upon Rome, though it appears nearly certain that a part of its population was of Etruscan origin, and that the two Tarquins represent the establishment of an Etruscan dynasty at Rome. The population of the city may therefore be regarded as one of mixed origin, consisting of the three elements of Latins, Sabines, and Etruscans, but the last in much smaller proportion than the other two. That the Latin element predominated over the Sabine is also evident from the fact that the language of the Romans was a Latin and not a Sabellian dialect.

The early history of Rome is given in an unbroken narrative by the Roman writers, and was received by the Romans themselves as a faithful record of facts. But it can no longer be regarded in that light. Not only is it full of marvelous tales and poetical embellishments, of contradictions and impossibilities, but it wants the very foundation upon which all history must be based. The reader, therefore, must not receive the history of the first four centuries of the city as a statement of undoubted facts, though it has unquestionably preserved many circumstances which did actually occur. It is not until we come to the war with Pyrrhus that we can place full reliance upon the narrative as a trustworthy statement of facts. With this caution we now proceed to relate the celebrated legends of the foundation and early history of Home.

Æneas, son of Anchises and Venus, fled after the fall of Troy to seek a new home in a foreign land. He carried with him his son Ascanius, the Penates or household gods, and the Palladium of Troy. Upon reaching the coast of Latium he was kindly received by Latinus, the king of the country, who gave him his daughter Lavinia in marriage. Æneas now built a city, which he named Lavinium, in honor of his wife. But Lavinia had been previously promised to Turnus, the leader of the Rutulians. This youthful chief, enraged at the insult, attacked the strangers. He was slain, however, by the hands of Æneas; but in a new war which broke out three years afterward the Trojan hero disappeared amid the waters of the River Numicius, and was henceforward worshiped under the name of Jupiter Indiges, or "god of the country"

Ascanius, who was also called Iulus, removed from Lavinium thirty years after its foundation, and built Alba Longa, or the "Long White City," on a ridge of the Alban Mount about fifteen miles southeast of Rome. It became the most powerful city in Latium, and the head of a confederacy of Latin cities. Twelve kings of the family of Æneas succeeded Ascanius. The last of these, named Procas, left two sons, Numitor and Amulius. Amulius, the younger, seized the kingdom; and Numitor, who was of a peaceful disposition, made no resistance to his brother. Amulius, fearing lest the children of Numitor might not submit so quietly to his usurpation, caused his only son to be murdered, and made his daughter, Rhea Silvia, one of the vestal virgins, who were compelled to live and die unmarried. But the maiden became, by the god Mars, the mother of twins. She was, in consequence, put to death, because she had broken her vow, and her babes were doomed to be drowned in the river. The Tiber had overflowed its banks far and wide; and the cradle in which the babes were placed was stranded at the foot of the Palatine, and overturned on the root of a wild fig-tree. A she-wolf, which had come to drink of the stream, carried them into her den hard by, and suckled them; and when they wanted other food, the woodpecker, a bird sacred to Mars, brought it to them. At length, this marvelous spectacle was seen by Faustulus, the king's shepherd, who took the children home to his wife, Acca Larentia. They were called Romulus and Remus, and grew up along with the sons of their foster-parents on the Palatine Hill.

A quarrel arose between them and the herdsmen of Numitor, who stalled their cattle on the neighboring hill of the Aventine. Remus was taken by a stratagem, and carried off to Numitor. His age and noble bearing made Numitor think of his grandsons; and his suspicions were confirmed by the tale of the marvelous nurture of the twin brothers. Soon afterward Romulus hastened with his foster-father to Numitor; suspicion was changed into certainty, and the old man recognized them as his grandsons. They now resolved to avenge the wrongs which their family had suffered. With the help of their faithful comrades they slew Amulius, and placed Numitor on the throne.

Romulus and Remus loved their old abode, and therefore left Alba to found a city on the banks of the Tiber. But a dispute arose between the brothers where the city should be built, and after whose name it should be called. Romulus wished to build it on the Palatine, Remus on the Aventine. It was agreed that the question should be decided by the gods; and each took his station on the top of his chosen hill, awaiting the pleasure of the gods by some striking sign. The night passed away, and as the day was dawning Remus saw six vultures; but at sunrise, when these tidings were brought to Romulus, twelve vultures flew by him. Each claimed the augury in his own favor; but the shepherds decided for Romulus, and Remus was therefore obliged to yield.

1. REIGN OF ROMULUS, B.C. 753-716. - Romulus now proceeded to mark out the boundaries of his city. He yoked a bullock and a heifer to a plow, and drew a deep furrow round the Palatine. This formed the sacred limits of the city, and was called the Pomœrium. To the original city on the Palatine was given the name of Roma Quadrata, or Square Rome, to distinguish it from the one which subsequently extended over the seven hills.

Rome is said to have been founded on the 21st of April, 753 years before the Christian era.

On the line of the Pomœrium Romulus began to raise a wall. One day Remus leapt over it in scorn; whereupon Romulus slew him, exclaiming, "So die whosoever hereafter shall leap over my walls" Romulus now found his people too few in numbers. Accordingly, lie set apart on the Capitoline Hill an asylum, or a sanctuary, in which homicides and runaway slaves might take refuge. The city thus became filled with men, but they wanted women, and the inhabitants of the neighboring cities refused to give their daughters to such an outcast race. Romulus accordingly resolved to obtain by force what he could not obtain by treaty. He proclaimed that games were to be celebrated in honor of the god Consus, and invited his neighbors, the Latins and Sabines, to the festival. Suspecting no treachery, they came in numbers with their wives and children, but the Roman youths rushed upon their guests and carried off the virgins. The parents returned home and prepared for vengeance. The inhabitants of three of the Latin towns, Cænina, Antemnæ and Crustumerium, took up arms one after the other, but were defeated by the Romans. Romulus slew with his own hand Acron, king of Cænina, and dedicated his arms and armor, as spolia opima, to Jupiter. These were offered when the commander of one army slew with his own hand the commander of another, and were only gained twice afterward in Roman history. At last Titus Tatius, the king of Cures, the most powerful of the Sabine states, marched against Rome. His forces were so great that Romulus, unable to resist him in the field, was obliged to retire into the city. Besides the city on the Palatine, Romulus had also fortified the top of the Capitoline Hill, which he intrusted to the care of Tarpeius. But his daughter Tarpeia, dazzled by the golden bracelets of the Sabines, promised to betray the hill to them "if they would give her what they wore on their left arms" Her offer was accepted. In the night-time she opened a gate and let in the enemy, but when she claimed her reward they threw upon her the shields "which they wore on their left arms," and thus crushed her to death. One of the heights of the Capitoline Hill preserved her name, and it was from the Tarpeian Rock that traitors were afterward hurled down. On the next day the Romans endeavored to recover the hill. A long and desperate battle was fought in the valley between the Palatine and the Capitoline. At one time the Romans were driven before the enemy, when Romulus vowed a temple to Jupiter Stator, the Stayer of Flight, whereupon his men took courage and returned again to the combat. At length the Sabine women, who were the cause of the war, rushed in between them, and prayed their husbands and fathers to be reconciled. Their prayers were heard; the two people not only made peace, but agreed to form only one nation. The Romans dwelt on the Palatine under their king Romulus, the Sabines on the Capitoline under their king Titus Tatius. The two kings and their senates met for deliberation in the valley between the two hills, which was hence called Comitium, or the place of meeting, and which afterward became the Roman Forum. But this union did not last long. Titus Tatius was slain at Lavinium by some Latins to whom he had refused satisfaction for outrages committed by his kinsmen. Henceforward Romulus ruled alone over both Romans and Sabines. He reigned, in all, thirty-seven years. One day, as he was reviewing his people in the Campus Martius, near the Goat's Fool, the sun was suddenly eclipsed, and a dreadful storm dispersed the people. When daylight returned Romulus had disappeared, for his father Mars had carried him up to heaven in a fiery chariot. Shortly afterward he appeared in more than mortal beauty to the senator Proculus Sabinus, and bade him tell the Romans to worship him under the name of the god Quirinus.

Plan of the City of Romulus

As Romulus was regarded as the founder of Rome, its most ancient political institutions and the organization of the people were ascribed to him by the popular belief.

(i.) The Roman people consisted only of Patricians and their Clients. The Patricians formed the Populus Romanus, or sovereign people. They alone had political rights; the Clients were entirely dependent upon them. A Patrician had a certain number of Clients attached to him personally. To these he acted as a Patronus or Patron. He was bound to protect the interests of the Client both in public and private, while the Client had to render many services to his patron.

(ii.) The Patricians were divided by Romulus into three Tribes; the Ramnes, or Romans of Romulus; the Tities, or Sabines of Titus Tatius; and the Luceres, or Etruscans of Cæles, a Lucumo or Etruscan noble, who assisted Romulus in the war against the Sabines. Each tribe was divided into 10 curiæ, and each curiæ into 10 gentes. The 30 curiæ formed the Comitia Curiata, a sovereign assembly of the Patricians. This assembly elected the king, made the laws, and decided in all cases affecting the life of a citizen.

To assist him in the government Romulus selected a number of aged men, forming a Senate, or Council of Elders, who were called Patres, or Senators. It consisted at first of 100 members, which number was increased to 200 when the Sabines were incorporated in the state. The 20 curiæ of the Ramnes and Tities each sent 10 members to the senate, but the Luceres were not yet represented.

(iii.) Each of the three tribes was bound to furnish 1000 men for the infantry and 100 men for the cavalry. Thus 3000 foot-soldiers and 300 horse-soldiers formed the original army of the Roman state, and were called a Legion.

2. REIGN OF NUMA POMPILIUS, B.C. 716-673. - On the death of Romulus, the Senate, at first, would not allow the election of a new king. The Senators enjoyed the royal power in rotation as Inter-reges, or between-kings. In this way a year passed. But the people at length insisted that a king should be chosen, and the Senate were obliged to give way. The choice fell upon the wise and pious Numa Pompilius, a native of the Sabine Cures who had married the daughter of Tatius. The forty-three years of Numa's reign glided away in quiet happiness without any war or any calamity.

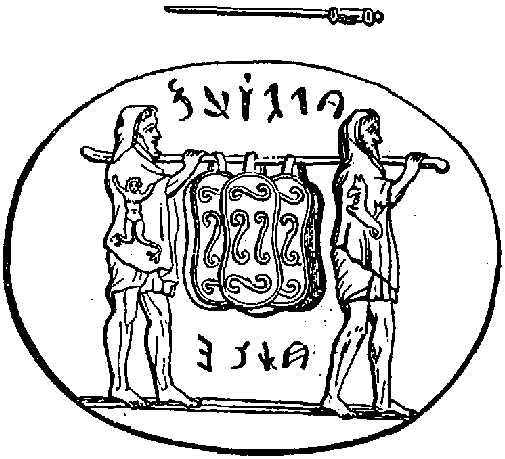

As Romulus was the founder of the political institutions of Rome, so Numa was the author of the religious institutions. Instructed by the nymph Egeria, whom he met in the sacred grove of Aricia, he instituted the Pontiffs, four in number, with a Pontifex Maximus at their head, who had the general superintendence of religion; the Augurs, also four in number, who consulted the will of the gods on all occasions, both private and public; three Flamens, each of whom attended to the worship of separate deities - Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus; four Vestal Virgins, who kept alive the sacred fire of Vesta brought from Alba Longa; and twelve Salii, or priests of Mars, who had the care of the sacred shields. Numa reformed the calendar, encouraged agriculture, and marked out the boundaries of property, which he placed under the care of the god Terminus. He also built the temple of Janus, a god represented with two heads looking different ways. The gates of this temple were to be open during war and closed in time of peace.

Salii carrying the Ancilia

3. REIGN OF TULLUS HOSTILIUS, B.C. 673-641. - Upon the death of Numa an interregnum again followed; but soon afterward Tullus Hostilius, a Roman, was elected king. His reign was as warlike as that of Numa had been peaceful. The most memorable event in it is the destruction of Alba Longa. A quarrel having arisen between the two cities, and their armies having been drawn up in array against each other, the princes determined to avert the battle by a combat of champions chosen from each army. There were in the Roman army three brothers, born at the same birth, named Horatii; and in the Alban army, in like manner, three brothers, born at the same birth, and called Curiatii. The two sets of brothers were chosen as champions, and it was agreed that the people to whom the conquerors belonged should rule the other. Two of the Horatii were slain, but the three Curiatii were wounded, and the surviving Horatius, who was unhurt, had recourse to stratagem. He was unable to contend with the Curiatii united, but was more than a match for each of them separately. Taking to flight, he was followed by his three opponents at unequal distances. Suddenly turning round, he slew, first one, then the second, and finally the third. The Romans were declared the conquerors, and the Albans their subjects. But a tragical event followed. As Horatius was entering Rome, bearing his threefold spoils, his sister met him, and recognized on his shoulders the cloak of one of the Curiatii, her betrothed lover. She burst into such passionate grief that the anger of her brother was kindled, and, stabbing her with his sword, he exclaimed, "So perish every Roman woman who bewails a foe" For this murder he was condemned by the two judges of blood to be hanged upon the fatal tree, but he appealed to the people, and they gave him his life.

Shortly afterward Tullus Hostilius made war against the Etruscans of Fidenæ and Veii. The Albans, under their dictator Mettius Fuffetius, followed him to the war as the subjects of Rome. In the battle against the Etruscans, the Alban dictator, faithless and insolent, withdrew to the hills, but when the Etruscans were defeated he descended to the plain, and congratulated the Roman king. Tullus pretended to be deceived. On the following day he summoned the two armies to receive their praises and rewards. The Albans came without arms, and were surrounded by the Roman troops. They then heard their sentence. Their dictator was to be torn in pieces by horses driven opposite ways; their city was to be razed to the ground; and they themselves, with their wives and children, transported to Rome. Tullus assigned to them the Cælian Hill for their habitation. Some of the noble families of Alba were enrolled among the Roman patricians, but the great mass of the Alban people were not admitted to the privileges of the ruling class. They were the origin of the Roman Plebs, who were thus quite distinct from the Patricians and their Clients. The Patricians still formed exclusively the Populus, or Roman people, properly so called. The Plebs were a subject-class without any share in the government.

After carrying on several other wars Tullus fell sick, and sought to win the favor of the gods, as Numa had done, by prayers and divination. But Jupiter was angry with him, and smote him and his whole house with fire from heaven. Thus perished Tullus, after a reign of thirty-two years.

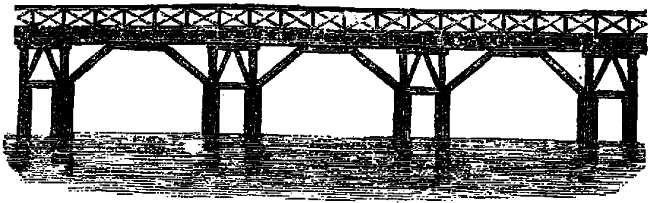

4. REIGN OF ANCUS MARCIUS, B.C. 640-616. - Ancus Marcius, the successor of Tullus Hostilius, was a Sabine, being the son of Numa's daughter. He sought to tread in the footsteps of his grandfather by reviving the religious ceremonies which had fallen into neglect; but a war with the Latins called him from the pursuits of peace. He conquered several of the Latin cities, and removed many of the inhabitants to Rome, where he assigned them the Aventine for their habitation. Thus the number of the Plebeians was greatly enlarged. Ancus instituted the Fetiales, whose duty it was to demand satisfaction from a foreign state when any dispute arose, to determine the circumstances under which hostilities might be commenced, and to perform the proper religious rites on the declaration of war. He also founded a colony at Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber, built a fortress on the Janiculum as a protection against the Etruscans, and united it with the city by a bridge across the Tiber, called the Pons Sublicius, because it was made of wooden piles, and erected a prison to restrain offenders. He died after a reign of twenty-four years.

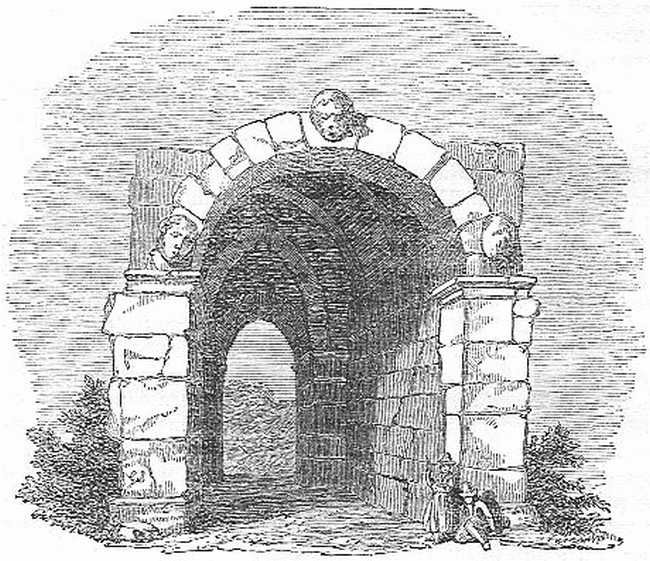

Arch of Volaterræ

Pons Sublicius, restored by Canina

Roman Empire History

- Geography Of Italy - Early Inhabitants

- The First Four Kings Of Rome - b.C. 753-616

- The Last Three Kings Of Rome, And The Establishment Of The Republic Down To The Battle Of The Lake Regillus - b.C. 616-498

- From The Battle Of The Lake Regillus To The Decemvirate - b.C. 498-451

- The Decemvirate - b.C. 451-449

- From The Decemvirate To The Capture Of Rome By The Gauls - b.C. 448-390

- From The Capture Of Rome By The Gauls To The Final Union Of The Two Orders - b.C. 390-367

- From The Licinian Rogations To The End Of The Samnite Wars - b.C. 367-290

- From The Conclusion Of The Samnite War To The Subjugation Of Italy - b.C. 290-265

- The First Punic War - b.C. 264-241

- Events Between The First And Second Punic Wars - b.C. 240-210

- The Second Punic War: First Period, Down To The Battle Of Cannae - b.C. 218-216

- Second Punic War: Second Period, From The Revolt Of Capua To The Battle Of The Metaurus - b.C. 215-207

- Second Punic War. Third Period: From The Battle Of The Metaurus To The Conclusion Of The War - b.C. 206-201

- Wars In The East. The Macedonian, Syrian, And Galatian Wars - b.C. 214-188

- Wars In The West. The Gallic, Ligurian, And Spanish Wars - b.C. 200-175

- The Roman Constitution And Army

- Internal History Of Rome During The Macedonian And Syrian Wars. Cato And Scipio

- The Third Macedonian, Achaean, And Third Punic Wars - b.C. 179-146

- Spanish Wars, b.C. 153-133. First Servile War, b.C. 134-132

- The Gracchi - b.C. 133-121

- Jugurtha And His Times - b.C. 118-104

- The Cimbri And Teutones, b.C. 113-101. - Second Servile War In Sicily, b.C. 103-101

- Internal History Of Rome From The Defeat Of The Cimbri And Teutones To The Social War - b.C. 100-91

- The Social Or Marsic War - b.C. 90-89

- First Civil War - b.C. 88-86

- First Mithridatic War - b.C. 88-84

- Second Civil War. - Sulla's Dictatorship, Legislation, And Death, b.C. 83-78

- From The Death Of Sulla To The Consulship Of Pompey And Crassus - b.C. 78-70

- Third Or Great Mithridatic War - b.C. 74-61

- Internal History, From The Consulship Of Pompey And Crassus To The Return Of Pompey From The East. - The Conspiracy Of Catiline - b.C. 69-61

- From Pompey's Return From The East To Cicero's Banishment And Recall. b.C. 62-57

- Caesar's Campaigns In Gaul - b.C. 58-50

- Internal History, From The Return Of Cicero From Banishment To The Commencement Of The Civil War. - Expedition And Death Of Crassus - b.C. 57-50

- From The Beginning Of The Second Civil War To Caesar's Death - b.C. 49-44

- From The Death Of Caesar To The Battle Of Philippi - b.C. 44-42

- From The Battle Of Philippi To The Battle Of Actium - b.C. 41-30

- Sketch Of The History Of Roman Literature, From The Earliest Times To The Death Of Augustus

- The Reign Of Augustus Caesar - b.C. 31-a.d. 14

- From The Accession Of Tiberius, A.D. 14-37, To Domitian, A.D. 96

- Prosperity Of The Empire, A.D. 96. - Commodus, A.D. 180. - Reign Of M. Cocceius Nerva, A.D. 96-98

- From Pertinax To Diocletian - A.D. 192-284

- From Diocletian, A.D. 284, To Constantine's Death, A.D. 337

- From The Death Of Constantine, A.D. 337, To Romulus Augustulus, A.D. 476

- Roman Literature Under The Empire - A.D. 14-476

The Rise of Rome

- Geography Of Italy - Early Inhabitants

- The First Four Kings Of Rome - b.C. 753-616

- The Last Three Kings Of Rome, And The Establishment Of The Republic Down To The Battle Of The Lake Regillus - b.C. 616-498

- From The Battle Of The Lake Regillus To The Decemvirate - b.C. 498-451

- The Decemvirate - b.C. 451-449

The Fall of Rome

- From The Death Of Caesar To The Battle Of Philippi - b.C. 44-42

- From The Battle Of Philippi To The Battle Of Actium - b.C. 41-30

- Sketch Of The History Of Roman Literature, From The Earliest Times To The Death Of Augustus

- The Reign Of Augustus Caesar - b.C. 31-a.d. 14

- From The Accession Of Tiberius, A.D. 14-37, To Domitian, A.D. 96

Roman Empire | Sitemap | | Contact Us | Disclaimer & Credits