First Mithridatic War - b.C. 88-84

The kingdom of Pontus, which derived its name from being on the coast of the Pontus Euxinus, or Black Sea, was originally a satrapy of the Persian empire, extending from the River Halys on the west to the frontiers of Colchis on the east. Even under the later Persian kings the rulers of Pontus were really independent, and in the wars of the successors of Alexander the Great it became a separate kingdom. Most of its kings bore the name of Mithridates; and the fifth monarch of this name formed an alliance with the Romans, and was rewarded with the province of Phrygia for the services he had rendered them in the war against Aristonicus. He was assassinated about B.C. 120, and was succeeded by his son Mithridates VI., commonly called the Great, who was then only about twelve years of age. His youth was remarkable, but much that has been transmitted to us respecting this period of his life wears a very suspicious aspect; it is certain, however, that when he attained to manhood he was not only endowed with consummate skill in all martial exercises, and possessed of a bodily frame inured to all hardships, but his naturally vigorous intellect had been improved by careful culture. As a boy he had been brought up at Sinope, where he had probably received the elements of a Greek education, and so powerful was his memory that he is said to have learned not less than twenty-five languages, and to have been able in the days of his greatest power to transact business with the deputies of every tribe subject to his rule in their own peculiar dialect. As soon as he was firmly established on the throne he began to turn his arms against the neighboring nations. On the west his progress was hemmed in by the power of Rome, and the minor sovereigns of Bithynia and Cappadocia enjoyed the all-powerful protection of the Republic. But on the east his ambition found free scope. He subdued the barbarian tribes between the Euxine and the confines of Armenia, including the whole of Colchis and the province called Lesser Armenia; and he even added to his dominions the Tauric Chersonesus, now called the Crimea. The Greek kingdom of Bosphorus, which formed a portion of the Chersonesus, likewise submitted to his sway. Moreover, he formed alliances with Tigranes, king of Armenia, to whom he gave his daughter Cleopatra in marriage, as well as with the warlike nations of the Parthians and Iberians. He thus found himself in possession of such great power and extensive resources, that he began to deem himself equal to a contest with Rome itself. Many causes of dissension had already arisen between them. Shortly after his accession, the Romans had taken advantage of his minority to wrest from him the province of Phrygia. In B.C. 93 they resisted his attempt to place upon the throne of Cappadocia one of his own nephews, and appointed a Cappadocian named Ariobarzanes to be king of that country. For a time Mithridates submitted; but the death of Nicomedes II., king of Bithynia, shortly afterward, at length brought matters to a crisis. That monarch was succeeded by his eldest son, Nicomedes III.; but Mithridates took the opportunity to set up a rival claimant, whose pretensions he supported with an army, and quickly drove Nicomedes out of Bithynia (B.C. 90). About the same time he openly invaded Cappadocia, and expelled Ariobarzanes from his kingdom, establishing his own son Ariarathes in his place. Both the fugitive princes had recourse to Rome, where they found ready support; a decree was passed that Nicomedes and Ariobarzanes should be restored to their respective kingdoms, and the execution of it was confided to M. Aquillius and L. Cassius.

Mithridates again yielded, and the two fugitive kings were restored to their dominions; but no sooner was Nicomedes replaced on the throne of Bithynia than he was urged by the Roman legates to invade the territories of Mithridates, into which he made a predatory incursion. Mithridates offered no resistance, but sent to the Romans to demand satisfaction, and it was not until his embassador was dismissed with an evasive answer that he prepared for immediate hostilities (B.C. 88). His first step was to invade Cappadocia, from which he easily expelled Ariobarzanes once more. His generals drove Nicomedes out of Bithynia, and defeated Aquillius. Mithridates, following up his advantage, not only made himself master of Phrygia and Galatia, but invaded the Roman province of Asia. Here the universal discontent of the inhabitants, caused by the oppression of the Roman governors, enabled him to overrun the whole province almost without opposition. The Roman officers, who had imprudently brought this danger upon themselves, were unable to collect any forces to oppose his progress; and Aquillius himself, the chief author of the war, fell into the hands of the King of Pontus. Mithridates took up his winter quarters at Pergamus, where he issued the sanguinary order to all the cities of Asia to put to death on the same day all the Roman and Italian citizens who were to be found within their walls. So hateful had the Romans rendered themselves during the short period of their dominion, that these commands were obeyed with alacrity by almost all the cities of Asia. Eighty thousand persons are said to have perished in this fearful massacre.

The success of Mithridates encouraged the Athenians to declare against Rome, and the king accordingly sent his general Archelaus with a large army and fleet into Greece. Most of the Grecian states now declared in favor of Mithridates. Such was the position of affairs when Sulla landed in Epirus in B.C. 87. He immediately marched southward, and laid siege to Athens and the Piræus. But for many months these towns resisted all his attacks. Athens was first taken in the spring of the following year; and Archelaus, despairing of defending the Piræus any longer, withdrew into Bœotia, where he received some powerful re-enforcements from Mithridates. Piræus now fell into the hands of Sulla, and both this place and Athens were treated with the utmost barbarity. The soldiers were indulged in indiscriminate slaughter and plunder. Having thus wreaked his vengeance upon the unfortunate Athenians, Sulla directed his arms against Archelaus in Bœotia, and defeated him with enormous loss at Chæronea. Out of the 110,000 men of which the Pontic army consisted, Archelaus assembled only 10,000 at Chalcis, in Eubœa, where he had taken refuge. Mithridates, on receiving news of this great disaster, immediately set about raising fresh troops, and was soon able to send another army of 80,000 men to Eubœa. But he now found himself threatened with danger from a new and unexpected quarter. While Sulla was still occupied in Greece, the party of Marius at Rome had sent a fresh army to Asia under the Consul L. Valerius Flaccus to carry on the war at once against their foreign and domestic enemies. Flaccus was murdered by his troops at the instigation of Fimbria, who now assumed the command, and gained several victories over Mithridates and his generals in Asia (B.C. 85). About the same time the new army, which the king had sent to Archelaus in Greece, was defeated by Sulla in the neighborhood of Orchomenus. These repeated disasters made Mithridates anxious for peace, but it was not granted by Sulla till the following year (B.C. 84), when he had crossed the Hellespont in order to carry on the war in Asia. The terms of peace were definitely settled at an interview which the Roman general and the Pontic king had at Dardanus, in the Troad. Mithridates consented to abandon all his conquests in Asia, to restrict himself to the dominions which he held before the commencement of the war, or pay a sum of 5000 talents, and surrender to the Romans a fleet of seventy ships fully equipped. Thus terminated the First Mithridatic War.

Sulla was now at liberty to turn his aims against Fimbria, who was with his army at Thyatira. The name of Sulla carried victory with it. The troops of Fimbria deserted their general, who put an end to his own life. Sulla now prepared to return to Italy. After exacting enormous sums from the wealthy cities of Asia, he left his legate, L. Licinius Murena, in command of that province, with two legions, and set sail with his own army to Athens. While preparing for his deadly struggle in Italy, he did not lose his interest in literature. He carried with him from Athens to Rome the valuable library of Apellicon of Teos, which contained most of the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus.

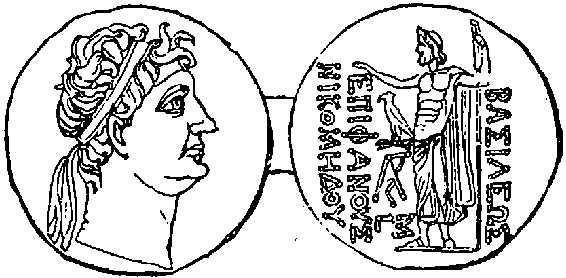

Coin of Nicomedes III., king of Bithynia

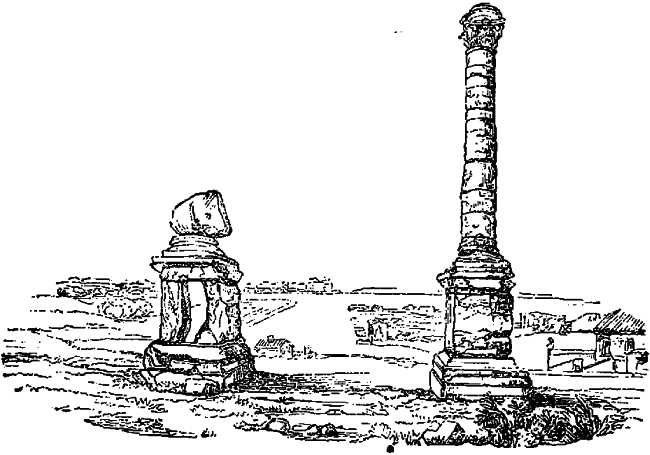

Brundisium

Roman Empire History

- Geography Of Italy - Early Inhabitants

- The First Four Kings Of Rome - b.C. 753-616

- The Last Three Kings Of Rome, And The Establishment Of The Republic Down To The Battle Of The Lake Regillus - b.C. 616-498

- From The Battle Of The Lake Regillus To The Decemvirate - b.C. 498-451

- The Decemvirate - b.C. 451-449

- From The Decemvirate To The Capture Of Rome By The Gauls - b.C. 448-390

- From The Capture Of Rome By The Gauls To The Final Union Of The Two Orders - b.C. 390-367

- From The Licinian Rogations To The End Of The Samnite Wars - b.C. 367-290

- From The Conclusion Of The Samnite War To The Subjugation Of Italy - b.C. 290-265

- The First Punic War - b.C. 264-241

- Events Between The First And Second Punic Wars - b.C. 240-210

- The Second Punic War: First Period, Down To The Battle Of Cannae - b.C. 218-216

- Second Punic War: Second Period, From The Revolt Of Capua To The Battle Of The Metaurus - b.C. 215-207

- Second Punic War. Third Period: From The Battle Of The Metaurus To The Conclusion Of The War - b.C. 206-201

- Wars In The East. The Macedonian, Syrian, And Galatian Wars - b.C. 214-188

- Wars In The West. The Gallic, Ligurian, And Spanish Wars - b.C. 200-175

- The Roman Constitution And Army

- Internal History Of Rome During The Macedonian And Syrian Wars. Cato And Scipio

- The Third Macedonian, Achaean, And Third Punic Wars - b.C. 179-146

- Spanish Wars, b.C. 153-133. First Servile War, b.C. 134-132

- The Gracchi - b.C. 133-121

- Jugurtha And His Times - b.C. 118-104

- The Cimbri And Teutones, b.C. 113-101. - Second Servile War In Sicily, b.C. 103-101

- Internal History Of Rome From The Defeat Of The Cimbri And Teutones To The Social War - b.C. 100-91

- The Social Or Marsic War - b.C. 90-89

- First Civil War - b.C. 88-86

- First Mithridatic War - b.C. 88-84

- Second Civil War. - Sulla's Dictatorship, Legislation, And Death, b.C. 83-78

- From The Death Of Sulla To The Consulship Of Pompey And Crassus - b.C. 78-70

- Third Or Great Mithridatic War - b.C. 74-61

- Internal History, From The Consulship Of Pompey And Crassus To The Return Of Pompey From The East. - The Conspiracy Of Catiline - b.C. 69-61

- From Pompey's Return From The East To Cicero's Banishment And Recall. b.C. 62-57

- Caesar's Campaigns In Gaul - b.C. 58-50

- Internal History, From The Return Of Cicero From Banishment To The Commencement Of The Civil War. - Expedition And Death Of Crassus - b.C. 57-50

- From The Beginning Of The Second Civil War To Caesar's Death - b.C. 49-44

- From The Death Of Caesar To The Battle Of Philippi - b.C. 44-42

- From The Battle Of Philippi To The Battle Of Actium - b.C. 41-30

- Sketch Of The History Of Roman Literature, From The Earliest Times To The Death Of Augustus

- The Reign Of Augustus Caesar - b.C. 31-a.d. 14

- From The Accession Of Tiberius, A.D. 14-37, To Domitian, A.D. 96

- Prosperity Of The Empire, A.D. 96. - Commodus, A.D. 180. - Reign Of M. Cocceius Nerva, A.D. 96-98

- From Pertinax To Diocletian - A.D. 192-284

- From Diocletian, A.D. 284, To Constantine's Death, A.D. 337

- From The Death Of Constantine, A.D. 337, To Romulus Augustulus, A.D. 476

- Roman Literature Under The Empire - A.D. 14-476

The Rise of Rome

- Geography Of Italy - Early Inhabitants

- The First Four Kings Of Rome - b.C. 753-616

- The Last Three Kings Of Rome, And The Establishment Of The Republic Down To The Battle Of The Lake Regillus - b.C. 616-498

- From The Battle Of The Lake Regillus To The Decemvirate - b.C. 498-451

- The Decemvirate - b.C. 451-449

The Fall of Rome

- From The Death Of Caesar To The Battle Of Philippi - b.C. 44-42

- From The Battle Of Philippi To The Battle Of Actium - b.C. 41-30

- Sketch Of The History Of Roman Literature, From The Earliest Times To The Death Of Augustus

- The Reign Of Augustus Caesar - b.C. 31-a.d. 14

- From The Accession Of Tiberius, A.D. 14-37, To Domitian, A.D. 96

Roman Empire | Sitemap | | Contact Us | Disclaimer & Credits